Has the Chinese Consumer Changed for Good? (Free to read - Part 1)

Profound changes in financial capabilities and expectations for future income have shifted consumers’ attitudes, with emotional satisfaction becoming a more important factor

Lackluster consumer spending has been a popular topic of discussion in post-pandemic China amid a weaker-than-expected economic recovery. The rise of low-price e-commerce platforms like Pinduoduo is often cited as evidence of this trend.

Yet, the reality of Chinese consumer behavior is complex. Some consumers are simultaneously splurging on high-end ski equipment while opting for more affordable domestic brands of cosmetics. Income levels do not solely dictate spending power. Instead, consumption encompasses both functional value and emotional satisfaction, with Chinese increasingly willing to pay for the latter.

There is nothing new about this. Historical data from the U.S. between 1986 and 2002 reveals that economically disadvantaged groups, such as African Americans and Hispanic Americans, spent 30% more on cars, clothing, jewelry and personal care products than their white counterparts with similar incomes. This disparity cannot be simply explained by living within one’s means, underscoring the emotional dimensions of consumption.

The past decade has witnessed numerous instances of emotional spending worldwide.

Following the global financial crisis, the Spring-Summer 2009 Paris Fashion Week proceeded as scheduled, with The New York Times likening the extravagance to the era of Marie Antoinette — a time when opulent fashion persisted despite widespread scarcity.

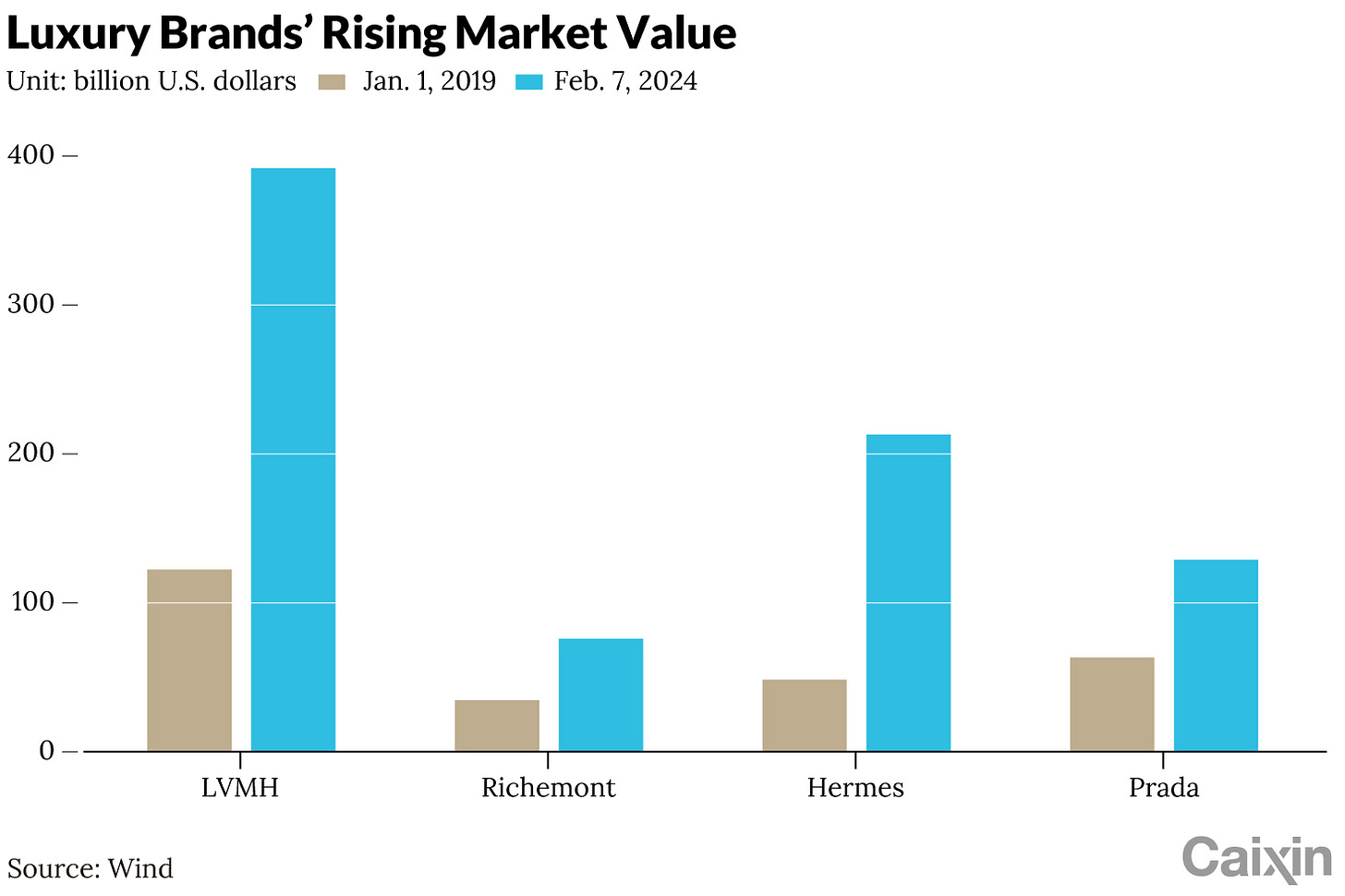

Post-pandemic, Hermès’ market value soared from $48.4 billion at the start of 2019 to $213.1 billion as of February 2024. With the Asia-Pacific region (excluding Japan) accounting for 48% of its revenue in the first three quarters of 2023, the company remains bullish on China’s mid to longterm growth potential, pushing forward with more store openings and expansions. Similarly, LVMH, home to a number of luxury brands, saw its market value skyrocket from $122.4 billion in early 2019 to $391.7 billion by February 2024. In 2023, Asia-Pacific (excluding Japan) revenue accounted for 31% of its total.

The cases of Hermès and LVMH show that the “consumption downgrade” trend seems less evident in China. Instead, these luxury giants’ booming sales in the face of the economic downturn suggests consumer aren’t particularly pessimistic.

This complex Chinese consumer behavior pattern highlights a nuanced reality: While certain segments of the population are tightening their belts, others are splashing out on luxury goods and things that meet emotional needs. As the global economy navigates a post-pandemic recovery, understanding the multifaceted nature of consumer trends — driven by both economic factors and emotional values — becomes crucial for businesses hoping to tap into China’s dynamic market.

What theories say

For companies seeking to decode these trends, it’s crucial to sift through various consumption theories to get a better sense of the situation. Let’s consider a few popular examples:

• Middle-class determinism: This perspective held sway for quite some time, with many companies developing strategies based on the assumption that China’s burgeoning middle-class consumer spending was here to stay.

• Upgrading vs. downgrading: The discourse eventually focused on whether consumption was being upgraded or downgraded, with the notion of a downgrade gaining traction, suggesting the middle-class spending patterns of the past had all but disappeared.

• M-shaped society: Introduced by William Ouchi in the 1980s, this theory suggests a polarization in consumption trends, with the majority of the middle class potentially sliding toward lower-income brackets.

• K-shaped Consumption: Proposed by The Economist, this concept describes post-pandemic consumers who either hunt for extreme bargains or splurge on luxury, indicating a split in the consumption patterns of the previously comfortable middle class.

Observing these theories reveals a common thread: they are predicated on income levels as the primary interpretive lens for consumer behavior. Yet, as discussed above, income alone does not define spending decisions. Consumption transcends basic survival needs to encompass psychological and social needs.