Hu Shuli Retraces Her Forebearers’ Wartime Footsteps in Indonesia (Part 2)

A Wartime Escape’ tells the story of group of Chinese intellectuals who fled from Singapore to Indonesia, where they lived in secret under Japanese occupation

At Payakumbuh, Yu Dafu found domestic bliss with Chen Lian, a young Indonesian-Chinese girl of modest beauty. He whimsically named her “He Liyou,” a play on words meaning “What beauty there is to have.”

Despite the chaos of war surrounding them, they were a pair of lovebirds, and on their wedding night, Yu Dafu penned four heartfelt poems. Chen Lian treasured these poems, unaware that her husband was a literary giant of the time. She bore Yu Dafu a son and a daughter, who was born just 12 hours after Yu Dafu was taken away by the Japanese soldiers. Never to see her father, the girl was named “Yu Meilan” by her mother.

After Yu Dafu vanished, Hu Yuzhi returned to Payakumbuh for more than 10 days, quizzing eyewitnesses and organizing a committee of local leaders and cultural figures to dig into Yu’s disappearance. Having reported the incident to the British Army and received promises of an investigation, Hu Yuzhi then returned to Singapore.

A year before his tragic end, Yu Dafu, perhaps sensing his fate, left a will entrusting the care of his children to a local Chinese leader in Payakumbuh, Cai Qingzhu. True to his word, after Yu Dafu’s demise, Cai arranged for the children to live and study in Jakarta. Cai himself moved back to China and settled in Xiamen in 1960, fortuitously avoiding the mass persecution of Chinese in Indonesia that was to come in 1965.

In 1955, after the Bandung Conference, China’s Deputy Minister of Culture Zheng Zhenduo visited Indonesia. Hu Yuzhi implored him to find Yu Dafu’s orphaned children. Zheng and Yu Dafu had a history working together, despite differing opinions. Despite past friction, the two men shared fundamental cultural values. Thanks to Zheng’s considerable efforts, Yu’s siblings were able to return to China in 1960. However, tragically, Zheng died in a plane crash en route to Afghanistan three years later.

In 1965, Yu’s daughter, Meilan, was admitted to a college in Beijing. On weekends, she stayed at Hu Yuzhi's home, where she met Hu’s nephew. They fell in love and married, thus Yu Meilan, the girl born amid the chaos of war in Sumatra, became Hu Shuli’s aunt by marriage.

While Yu Dafu was alive, he seemed to acknowledge the itinerant nature of his life, once reflecting: “Lone and adrift, braving a path through brambles and thorns. Fortunate to have friends within the four seas, stopping by their doors, I am moved by deep affection.” His words proved to be prophetic.

Undercover party member

Hu Yuzhi’s tale is one that cannot be fully told.

Many of his fellow democrats were unaware that he had become a secret member of the “Central Special Branch” of the Chinese Communist Party as early as September 1933. He did not participate in grassroots organizational activities and did not appear publicly to identify as a communist, his main task being intelligence work for the party.

The American scholar Edward Said studied the phenomenon of intellectual exile, proposing a distinction between “insiders” and “outsiders.” Yhere are those who belong entirely to their society, achieving success without strong dissent or objections, known as “yea-sayers.” Then there are the “nay-sayers,” who are at odds with society — outsiders and exiles in terms of reaping the power and glory.

Hu Yuzhi, born in turbulent times and standing as a free intellectual, was an “outsider” of his era. Yet, in the field of journalism and publishing, he was a leading figure with considerable influence among his peers.

After the establishment of People’s Republic of China in 1949, Hu became the first director of the General Administration of Publishing, later ascending to more politically important roles, such as vice chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference and vice chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress. He always maintained a critical and constructive stance in both good times and bad. But he still kept his secret.

In 1948, Zhou Enlai met Hu Yuzhi and asked him, “Are you still undercover or public now?” meaning whether his Party membership was known. Hu replied, “Still undercover.”

Zhou then instructed him: “You remain undercover and continue your work with the democratic parties. If you go public, you can come to work at the Xinhua News Agency.”

Days later, Zhou visited Hu's dormitory for a talk that lasted all night, urging him to stay focused on the united front work and remain undercover. Hu Yuzhi complied, remaining in the democratic parties as a secret Communist Party member.

Hu Yuzhi meets with Fei Xiaotong and his wife in Singapore in 1947. Photo: File photo

During China’s “Anti-Rightist Campaign” in 1957, Hu Yuzhi remained sympathetic toward the intellectuals being prosecuted, never harshly criticizing any member of the Democratic League or intellectual. Fei Xiaotong, a pioneer of Chinese anthropology, who suffered during the period that proved trying for many intellectuals, remarked that in the hardest days of the “10 years of chaos,” Hu Yuzhi always harbored concerns about the plight of intellectuals, especially the old comrades.

Hu is due some respect for his audacity during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

In 1972, amidst the upheaval, he, along with Mao Zedong’s former schoolmates, bravely requested an audience with Chairman Mao to report the societal problems they had observed. Mao said, “We can give the democrats a bit of democracy,” and instructed his trusted aides, Hua Guofeng and Wang Dongxing, to spend two afternoons listening to their views. Hu Yuzhi spoke of “promoting democracy and opening up for discussion,” and of restoring the activities of democratic parties where possible.

In October 1979, at the fourth plenary session of the Democratic League, Hu Yuzhi, representing the Central Committee of the League, reported on the work, touching on the “over-expansion of the Anti-Rightist” issue and especially the “leftist” mistakes made by the League. Hu deviated from his script to apologize to League comrades and intellectuals who had been politically implicated and unjustly treated. It was not until that year that the government publicly acknowledged the Communist Party membership of the then-83-year-old Hu Yuzhi.

Indonesia then and now

During their exile in Indonesia, Hu Yuzhi and his companions received heartfelt aid from the Chinese diaspora. Local Chinese brought their own beds tables, and chairs, while the elderly couple who owned the garden tirelessly made their beds and carried firewood for them.

After their return to China, the local Chinese community that remained behind endured two major calamities: the appalling anti-Chinese riots of 1965 and 1997, which were marked by looting and massacres. For about 30 years, the Chinese language was taboo, Chinese schools forced to close, and even the celebration of the Lunar New Year was banned. The tragedies bring a sense of deep sorrow and unrest when recalled.

However, entering the new century, Indonesia began a process of democratization, including embracing Chinese culture. In 2014, the Indonesian government abolished the pejorative term “Cina” from Suharto's 1967 decree, replacing it with “Tionghoa” to refer to the Chinese community.

On June 16, Hu Shuli poses next to a monument commemorating Indonesia’s independence from Japan in Pekanbaru, Indonesia. Photo: Yangmin/Caixin

On her journey, Hu Shuli encountered many elderly ladies who chatted in the southern Fujian dialect. In Bengkalis supermarkets, she saw children clamoring for Chinese brands of bubble tea and Chinese Oppo smartphone stores were everywhere — rounding out a scene of peace and prosperity.

Thinking back in time, during his exile in Indonesia, Hu Yuzhi told stories to local Chinese youths and wrote a science fiction novel titled “The Young Aviator: A Dreamwalk Through the Homeland.”

In his book, Hu addressed the children of New China and the Indonesian Chinese diaspora: “Always face the future, do not pine for the past, everything for tomorrow, do not be infatuated with yesterday.”

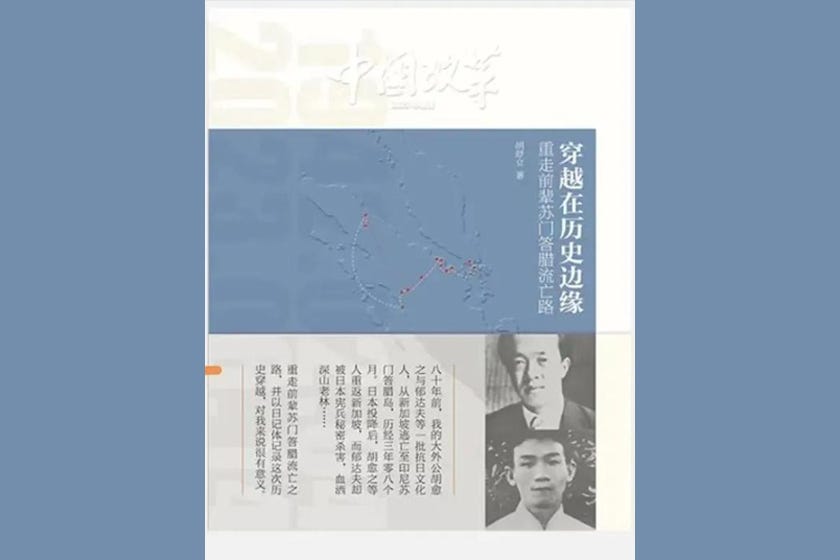

Caixin Media founder and Publisher Hu Shuli’s new book “A Wartime Escape — Retracing the Footprints of My Granduncle in Sumatra.”

Zhu Huaxin was an executive council member and director of internet and new economy studies at the China Society of Economic Reform, a national institute established in 1983 with a focus on the reform of China’s economic system. The article, edited for length and clarity, was first published in Chinese by Caixin.